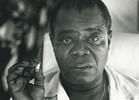

Louis Armstrong is considered the original American jazz musician, the voice and image of a New Orleans resident with a trumpet in one hand and a big smile on his face.

That smile is a problem for Sacha Jenkins, who directs Louis Armstrong's Black & Blues, a documentary on Apple TV+. Jenkins previoulsy helmed Bitchin': The Sound and Fury of Rick James.

Born in 1901, Armstrong was among the first Black Americans to create the jazz artform, which required musicians to improvise over a theme. He got his start with King Oliver's band and soon was in Chicago performing with the "cats," many of whom escaped the South for better opportunities up North.

Armstrong was raised by a woman, Mary, who "always believed in herbs." The laxative Swiss Kriss was long extoled by the trumpeter. So was marijuana.

A two-minute section starting at the 1:07 mark begins with him saying, "Let's talk about pot. Marijuana is more of a medicine than dope." A cannabis cup with Satchmo's name on it is shown, followed by smoking photos and a handwritten statement from the 1955 Jazz Musicians Drug Survey in which Armstrong complained, "Just leave the musicians alone. Whatever he's using is none of ours or nobody's business."

Jazz critic Dan Morganstern comments on Armstrong's use: "It relaxes you. It does something to your hearing and if you're a musician it does something to your playing."

Describing his 1931 pot arrest in Los Angeles, Armstong recalls: "It was during our intermission. Big healthy dicks, detectives that is, hid behind a car and said to us, 'We'll take that roach, boys.' I spent nine days in the downtown Los Angeles city jail. The judge gave me a suspended sentence and I went back to work like nothing happened."

No mention is made of a letter Armstrong wrote to Pres. Eisenhower calling for marijuana to be legalized in 1954.

But much is made of Armstrong's advocacy in general while the South remained segregated in the '50s and early '60s. He got involved in the protests in Arkansas in 1954. But otherwise Armstrong is depicted as standing on the sidelines while Blacks were being persecuted. Of course, Armstrong felt that persecution but he was able to rise above up, anointed by Cafe Society as an exception to the racist rule. He's perceived as performing for whites, shucking and jiving as he became more than just a jazz musician, a Hollywood star for all of America to watch on the silver screen.

Ossie Davis: "Most of the fellows I grew up with, we used to laugh at Louis Armstrong."

Miles Davis says, "They called him an Uncle Tom for being himself." Amari Baraka refers to Armstrong's submissiveness, affability and constant smiling.

But Armstrong responds, "When have I Uncle Tommed in my life?"

In the dictionary, Uncle Tom is defined as: "A black man considered to be excessively obedient or servile to white people... A person regarded as betraying their cultural or social allegiance."

The crux of the movie falls on actor Ossie Davis to explain: "Most of the fellows I grew up with, we used to laugh at Louis Armstrong. We knew he could play the horn, but that didn't save him from our malice and our ridicule. Everywhere we'd look, there would be ol' Louis - sweat poppin', eyes buggin', mouth wide open grinnin' oh my Lord from ear to ear. Oofta we would call it. Moppin' his brow, duckin' his head, doin' his thing for the white man, oh yeah!"

Davis' comtempt for Armstrong was tempered when they met on a movie set in 1966. He recalled a moment of sadness as Armstrong sat forlorn in his dressing room, but then snapping out it with his raspy voice and grin. "But it wasn't funny, not anynore," Davis says. "I never laughed at Louis after that."

Armstrong died in 1971 at 70 years old as U.S. soldiers fought in Vietnam and protestors called for an end to the war. He never quite fit in with the '60s radicals, but Armstrong was indeed a pioneer who fought for equal rights, but always with that famous smile.